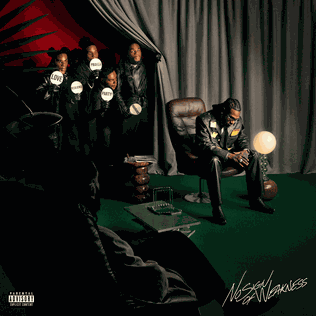

The past few days since Burna Boy released his long-awaited album on July 11 have been a mix of musical immersion and guilty pleasure. While I’ve taken time to listen repeatedly to No Sign of Weakness, I must also confess that my spare time has been dominated by Love Island, which ended with Amaya emerging as the winner. But to return to the matter at hand, Burna Boy’s No Sign of Weakness is, without question, a remarkably substantial body of work that deserves critical attention. As I listened to the album; whether while driving, doing chores, or multitasking through the day(s), two core themes that kept surfacing were Burna Boy’s assertion of a hegemonic posture and his profound, piercing, and sometimes disarming existential questioning.

The album opens with “No Panic,” a song that with its groovy and immersive beat, creates an ambiance that celebrates confidence while exuding unflinching dominance. In Nigerian parlance, “no panic” is commonly expressed to signal confidence, assurance, and/or control. Burna Boy, here, is once again staking his claim in the Afrobeats arena, declaring that he has nothing to panic about because he remains the “Giant” he’s always claimed to be, possessing everything more than “all of them.” He follows this with the album’s title track, “No Sign of Weakness,” which begins with a voice-over: “Weakness does not need permission to take over your life, it only needs space…” As expected, Burna distances himself from any form of weakness, rejecting it as a threat to his carefully nurtured image of dominance. But in “28 Grams,” we encounter a more composite Burna.

While the track still plays on his hegemonic identity through his invocation of weed culture, it simultaneously offers a surprising message of “moderation” and “mindfulness.” He reflects on life’s difficulties and suggests responsibility and caution, urging listeners to choose sensibly. The choice of “28 grams,” which is a full ounce of weed and also a symbolic weight, perhaps, gestures toward the burden of escape, indulgence, and even fame potentially. One may as well read the adoption of the title as a specific measure that hints at a measured approach, rather than unrestrained indulgence. Nevertheless, any subtle restraint in Burna’s hegemonic performance quickly dissolves in “Kabiyesi,” where he declares himself king outright to cement his status as an alpha.

When you consider the figure of a Kabiyesi – a Yoruba term of address used for a king, signifying reverence and majesty – and Burna’s recurrent refrain of telling everyone to say “Kabiyesi, olori olola” (meaning ‘King, owner of wealth/honor’ or ‘King, the most glorious’), it’s clear he’s elevating himself further. Burna has already claimed the Igbo title “Odogwu” (meaning ‘great man’ or ‘champion’); now, by embracing “Kabiyesi,” he’s taking another powerful step into Yoruba cultural royalty. It almost makes you wonder if a later track might feature a term from Hausa culture referring to a man of equally high, if not the highest, status to complete his symbolic conquest of Nigerian ethnic hegemonies.

However, besides the hegemonic performances and aspirations that dot the album, its existential undercurrent persists and takes center stage in introspective tracks like “Buy You Life.” In this song, Burna preaches the importance of allowing oneself to be led by light and finding one’s way home. While critiquing the relentless pursuit of wealth, Burna Boy ironically warns against a life consumed by money, warning of the emptiness that comes from this obsessive chase of money, even as he later ironically acknowledges his indulgence in material vanity on “Bundle” due to his financial largeness. In “Buy You Life,” he offers a striking counterpoint, declaring that wealth cannot buy life itself and urging listeners to follow the light and find their way home.

The existentialist component of the song continues in ‘Empty Chairs,” featuring Mick Jagger, where Burna delivers more philosophical reflections and punches even harder on the absurdity of life: “You might think you’re sitting on a throne, but to me it’s just an empty chair.” He questions the futility of status, even as he clings to it himself. Declaring himself a general who cannot cry, he reveals that “all is not what you think,” hinting that it might all be a dream. He even proceeds to critique the illusion of upward mobility and jab at societal structures, singing: “This world na housing scheme, if you’re poor you be victim of profiling, if you no be politician and you manage get rich…” This song genuinely makes you pause and reflect on your own life, especially when confronting systemic barriers to advancement, prompting a deep self-assessment of your current standing. It’s quite profound. Right?

In “Pardon,” featuring Stromae, Burna explores imperfection and human fallibility. The track renders vulnerability in soft, rhythmic cadences, resounding the existential condition of being flawed and finite; the inherent fallibility of human existence. The album also touches on a romantic flair with different existential dimensions. In “Come Gimme,” he expresses longing, a yearning for warmth and affection, while “Love” offers a bleaker view. There, Burna critiques the needlessness of trying to impress others and admits that only a few will truly love you. He notes hauntingly that no matter how much you love people, only a select few will truly reciprocate, then declares that he has turned his mind “into a weapon,” and hence, will only love those who love him. This brings to mind Jean-Paul Sartre’s famous existentialist idea, “l’enfer c’est l’autre” (hell is other people), suggesting that our self-awareness and freedom are often constrained or revealed through the gaze and judgment of others, and the relationships that should serve as sites of refuge are rather filled with thorns and anguish.

In “Dem Dey,” Burna ingeniously repurposes public controversy surrounding his promise of a Lambo for a “love affair” into a song, launching into a romantic amour with the reggae-infused “Sweet Love,” where he serenades with the full glam of a confident lover singing, “I want to give you love, sweet, sweet love.” Considering Burna’s Twitter post where he stated, “They said I needed to talk about my thoughts and feelings, but I made an album instead,” it becomes clear that No Sign of Weakness wasn’t primarily designed for anyone’s pleasure but rather as an arena for him to express and process his deepest thoughts.

Overall, I submit that Burna Boy’s No Sign of Weakness is a significant philosophical and existential piece, despite its dominant hegemonic posture. While it has a few minor weaknesses such as a slight drag between some songs and beats that occasionally feel too similar to previous works (like “Buy You Life” somewhat replicating “Common Person” in both sound and philosophical stance), I believe Burna ultimately achieved his stated goal of airing his thoughts. Especially when you listen to tracks like “Love,” you can feel the pain in his heart and hear his vulnerability. He may lay claim to being Odogwu and Kabiyesi, but at the end of the day, Burna is just a man going through life, its flows, and turbulences. And perhaps that is the whole point; that beneath all the bravado, the crowns, the ganja, and the grooves, he is just trying to live. After all, he is only human.